Thursday, May 29, 2008

Tampa's Plant Field, April 4, 1919: The spring training home run that changed baseball history...forever!

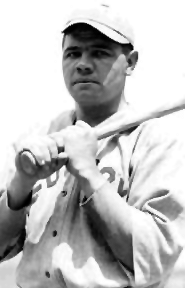

With one swing of the bat on an April afternoon in 1919 in Tampa, George Herman "Babe" Ruth changed the course of American sports history.

As pitcher for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, Ruth had emerged as the American League's premier left-hander, winning 78 games and leading his team to two World Series titles.

But Babe loved to hit and wanted to play every day. Team owner Harry Frazee disagreed.

When the team arrived in Tampa for spring training in March of 1919, Ruth wasn't among them, holding out for $15,000--an unheard of salary. And he wanted to play outfield, not pitch.

With the rest of the team in Tampa, Frazee and Ruth met in New York and came to terms: $10,000 a year for three years...but Ruth would stay on the mound. Babe signed, then caught the midnight train to Tampa.

He arrived in time for Boston's first exhibition game, on Friday, April 4 against the New York Giants, to be played at Plant Field, located on the site of the current McKay Auditorium at the University of Tampa. Bases had been laid out on the vast grounds of a racetrack.

At 4:15pm Friday, Billy Sunday, the nation's leading evangelist, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. (Sunday, himself a former big leaguer, was in town for a tent revival).

Ruth led off the bottom of the second. Giants pitcher George Smith hurled a fastball down the middle. Gripping the bat so far down the handle his right pinky actually hung off the butt-end, like a society matron sipping tea, the Babe swung and the ball rocketed toward right field. Giants outfielder Ross Youngs turned and ran, but halfway to the fence he stopped. The ball was still climbing. It bounced clear across the race track and rolled to a stop. A youngster retrieved the ball.

After the game, won by Boston 5 to 3, sportswriters asked Youngs to show them where Ruth's ball had come to rest. Laboriously, the writers paced the distance back to home plate.

The phrase "tape-measure shot" hadn't been invented yet, but it soon would be. The blast measured somewhere between 587 to 600 feet. Even Giants' manager John McGraw, a crusty old bird not given to hyperbole, called it "the longest ball I've ever seen hit."

It was the longest ball anyone could ever remember seeing hit. And by a pitcher! Later that evening, the ball--signed by Babe and Barrow--was presented to Billy Sunday at his tent.

Headlines in Saturday's Tampa Tribune screamed: "RUTH DRIVES GIANTS TO DEFEAT AND MAKES 'EM DRINK, TOO, B'GADS." The reporter, calling Ruth's homer a "wallop stupendous," wrote: "The Giants were still marveling last night. Many of them have never seen the Tarzan

perform since he annexed his slugging habits."

Monday, April 7, the Red Sox broke camp and headed north, barnstorming along the way with games in Gainesville, Winston-Salem, Charleston. In every town, huge crowds buzzed about mighty Babe and his blast. Frazee was becoming convinced: Babe needed to play every day.

During the 1919 season Babe pitched 17 games, but it was his final season on the mound. Playing outfield for Boston on days he didn't pitch, Ruth hit an astounding 29 home runs. That may not seem like much to today's fan. But consider: Before 1919, the single-season record for homers was 24, held by Gabby Cravath of the Philadelphia Phillies. In 1920, playing every day, Babe hit more homers (54) than any entire team in the American League! By the time he retired in 1935, Ruth had hit more homers than any man in the game's history.

Plant Stadium was razed in 2002 and replaced with a modern edifice, but a plaque on campus commemorates that historic swing of the bat on an April afternoon in Tampa, a swing that transformed the legend of Babe Ruth--and American sports--forever.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 18

As pitcher for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, Ruth had emerged as the American League's premier left-hander, winning 78 games and leading his team to two World Series titles.

But Babe loved to hit and wanted to play every day. Team owner Harry Frazee disagreed.

When the team arrived in Tampa for spring training in March of 1919, Ruth wasn't among them, holding out for $15,000--an unheard of salary. And he wanted to play outfield, not pitch.

With the rest of the team in Tampa, Frazee and Ruth met in New York and came to terms: $10,000 a year for three years...but Ruth would stay on the mound. Babe signed, then caught the midnight train to Tampa.

He arrived in time for Boston's first exhibition game, on Friday, April 4 against the New York Giants, to be played at Plant Field, located on the site of the current McKay Auditorium at the University of Tampa. Bases had been laid out on the vast grounds of a racetrack.

At 4:15pm Friday, Billy Sunday, the nation's leading evangelist, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. (Sunday, himself a former big leaguer, was in town for a tent revival).

Ruth led off the bottom of the second. Giants pitcher George Smith hurled a fastball down the middle. Gripping the bat so far down the handle his right pinky actually hung off the butt-end, like a society matron sipping tea, the Babe swung and the ball rocketed toward right field. Giants outfielder Ross Youngs turned and ran, but halfway to the fence he stopped. The ball was still climbing. It bounced clear across the race track and rolled to a stop. A youngster retrieved the ball.

After the game, won by Boston 5 to 3, sportswriters asked Youngs to show them where Ruth's ball had come to rest. Laboriously, the writers paced the distance back to home plate.

The phrase "tape-measure shot" hadn't been invented yet, but it soon would be. The blast measured somewhere between 587 to 600 feet. Even Giants' manager John McGraw, a crusty old bird not given to hyperbole, called it "the longest ball I've ever seen hit."

It was the longest ball anyone could ever remember seeing hit. And by a pitcher! Later that evening, the ball--signed by Babe and Barrow--was presented to Billy Sunday at his tent.

Headlines in Saturday's Tampa Tribune screamed: "RUTH DRIVES GIANTS TO DEFEAT AND MAKES 'EM DRINK, TOO, B'GADS." The reporter, calling Ruth's homer a "wallop stupendous," wrote: "The Giants were still marveling last night. Many of them have never seen the Tarzan

perform since he annexed his slugging habits."

Monday, April 7, the Red Sox broke camp and headed north, barnstorming along the way with games in Gainesville, Winston-Salem, Charleston. In every town, huge crowds buzzed about mighty Babe and his blast. Frazee was becoming convinced: Babe needed to play every day.

During the 1919 season Babe pitched 17 games, but it was his final season on the mound. Playing outfield for Boston on days he didn't pitch, Ruth hit an astounding 29 home runs. That may not seem like much to today's fan. But consider: Before 1919, the single-season record for homers was 24, held by Gabby Cravath of the Philadelphia Phillies. In 1920, playing every day, Babe hit more homers (54) than any entire team in the American League! By the time he retired in 1935, Ruth had hit more homers than any man in the game's history.

Plant Stadium was razed in 2002 and replaced with a modern edifice, but a plaque on campus commemorates that historic swing of the bat on an April afternoon in Tampa, a swing that transformed the legend of Babe Ruth--and American sports--forever.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 18

Paradise Lost? The Ft. Lauderdale Spring Break Riots of 1967.

If teens in the Eisenhower-era didn't have an official Spring Break destination, the 1960 beach-blanket flick Where the Boys Are, shot on the sands of Ft. Lauderdale, surely gave them one. Starring Connie Francis and George Hamilton, the film produced box-office bling-bling and firmly established Ft. Lauderdale as collegians' bachnallian hot-spot.

Each year thereafter, spring breakers arrived in ever-increasing numbers, pumping millions into Ft. Lauderdale's economy. It was win-win.

All that changed, however, over the three-day Easter-weekend in 1967, when a full-scale riot erupted between spring breakers and police.

Trouble began on Friday, March 24, at the town's main drag, the intersection of Las Olas and Atlantic Boulevards. A group of famished students flagged down a passing bakery truck and helped themselves to bread and cakes. The group then commandeered a soft-drink truck, and looted its contents, too.

When police arrived in an attempt to restore order, events took an ugly turn: Empty bottles flew. Kids stomped over the tops of cars. A small mob surrounded a city bus, smashed out its windows, and rocked it with such force that it nearly overturned. Aboard, twevle occupants, including a mother and infant, scrambled to safety.

The crowd surged onto a side street and looted a fruit and vegetable stand. A paddy wagon arrived and police--now in full riot gear and dodging tomatoes and green peppers --made the first of 30 arrests.

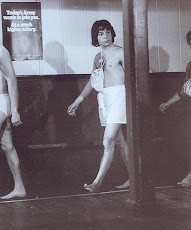

That evening, Police Chief Robert Johnson sent 200 cops on patrol, the youngest members working undercover by donning swimtrunks and mingling with the crowd.

Saturday morning's melee erupted as police observed a game of "blanket-toss," in which comely co-eds are bounced up and down on blankets, trampoline-style, by male admirers.

Cops attempted to break it up. Beer cans flew. A chant went up: "Ft. Lousydale pigs!" and "Police brutality!" Baton-swinging cops arrested offenders and hauled them to jail.

At the courthouse, Municipal Judge Stephen Booker, flooded with over 100 cases, promised to "stay until midnight if necessary." Most violators receved two nights lodging at city expense and a $50 fine.

Overhead, a plane towed a banner which read: "Welcome Collegians--Gilbert's Bail Bonds."

As night fell, city officials set up roadblocks at city bridges and turned back everyone without a beach address. Students headed for the bars. As the sun rose Easter morning, most of the town's 30,000 visitors, bleary-eyed from drink and sleep-depravation, were busy arranging transportation back to campus. "Hopefully," a cop told reporters, "the Easter spirit will prevail. But we're ready if it doesn't."

It didn't.

Another mele erupted. Once again, beer bottles sailed like frisbees. Again, police worked their way through the crowd flailing batons. Cops collared 20 kids and threw them into the paddy wagon. Halfway to jail, the wagon erupted in flames, the inferno ignited by a student with a cigarette lighter.

All told, Ft. Lauderdale's three-day riot resulted in over 500 arrests and hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage.

Eventually, Ft. Lauderdale would tire of hosting Spring Break. By the mid-1980s city fathers said: Enough. The city erected a wall to keep revelers contained to one side of the street. Breakers got the message and took their annual rite to more hospitable climes.

But it was the Riot of 1967 that provided Ft. Lauderdale's first glimpse at the ugly side of paradise, a wake-up call that times had changed: Modern teens, a product of the post-WWII baby boom, disdained authority and revelled in rebellion.

No doubt about it:

Connie Francis and George Hamilton they were not.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 20

Each year thereafter, spring breakers arrived in ever-increasing numbers, pumping millions into Ft. Lauderdale's economy. It was win-win.

All that changed, however, over the three-day Easter-weekend in 1967, when a full-scale riot erupted between spring breakers and police.

Trouble began on Friday, March 24, at the town's main drag, the intersection of Las Olas and Atlantic Boulevards. A group of famished students flagged down a passing bakery truck and helped themselves to bread and cakes. The group then commandeered a soft-drink truck, and looted its contents, too.

When police arrived in an attempt to restore order, events took an ugly turn: Empty bottles flew. Kids stomped over the tops of cars. A small mob surrounded a city bus, smashed out its windows, and rocked it with such force that it nearly overturned. Aboard, twevle occupants, including a mother and infant, scrambled to safety.

The crowd surged onto a side street and looted a fruit and vegetable stand. A paddy wagon arrived and police--now in full riot gear and dodging tomatoes and green peppers --made the first of 30 arrests.

That evening, Police Chief Robert Johnson sent 200 cops on patrol, the youngest members working undercover by donning swimtrunks and mingling with the crowd.

Saturday morning's melee erupted as police observed a game of "blanket-toss," in which comely co-eds are bounced up and down on blankets, trampoline-style, by male admirers.

Cops attempted to break it up. Beer cans flew. A chant went up: "Ft. Lousydale pigs!" and "Police brutality!" Baton-swinging cops arrested offenders and hauled them to jail.

At the courthouse, Municipal Judge Stephen Booker, flooded with over 100 cases, promised to "stay until midnight if necessary." Most violators receved two nights lodging at city expense and a $50 fine.

Overhead, a plane towed a banner which read: "Welcome Collegians--Gilbert's Bail Bonds."

As night fell, city officials set up roadblocks at city bridges and turned back everyone without a beach address. Students headed for the bars. As the sun rose Easter morning, most of the town's 30,000 visitors, bleary-eyed from drink and sleep-depravation, were busy arranging transportation back to campus. "Hopefully," a cop told reporters, "the Easter spirit will prevail. But we're ready if it doesn't."

It didn't.

Another mele erupted. Once again, beer bottles sailed like frisbees. Again, police worked their way through the crowd flailing batons. Cops collared 20 kids and threw them into the paddy wagon. Halfway to jail, the wagon erupted in flames, the inferno ignited by a student with a cigarette lighter.

All told, Ft. Lauderdale's three-day riot resulted in over 500 arrests and hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage.

Eventually, Ft. Lauderdale would tire of hosting Spring Break. By the mid-1980s city fathers said: Enough. The city erected a wall to keep revelers contained to one side of the street. Breakers got the message and took their annual rite to more hospitable climes.

But it was the Riot of 1967 that provided Ft. Lauderdale's first glimpse at the ugly side of paradise, a wake-up call that times had changed: Modern teens, a product of the post-WWII baby boom, disdained authority and revelled in rebellion.

No doubt about it:

Connie Francis and George Hamilton they were not.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 20

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

The Making of PT 109...How Hollywood helped spin the Kennedy legend

He was our nation's first cult president, an impossible combination of leading-man looks, political savvy, and boundless personal charm. Not surprisingly, he was the first living President of the United States to be the subject of a major motion picture.

The inside story of the making of that picture, PT 109--America's first marriage of presidential politics and Hollywood film-making--illustrates the principle that in Washington as in Tinseltown, it's all about the Art of the Spin.

The meteoric political rise of John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy--the protagonist of our tale--in fact began with a shamefaced debacle aboard patrol-torpedo boat 109 in the South Pacific during World War II. Kennedy was a 26-year-old Navy lieutenant in charge of the fast-moving, 80-foot PT boat, one of over 600 such vessels defending the South Pacific. In the moonless midnight blackness of August 1, 1943, Kennedy's 109 was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. Two of 12 crew members drowned; Kennedy led the survivors to safety, swimming island to island until help arrived.

The incident left Jack Kennedy deeply ashamed. He should have been: In the entire history of World War II, the 109 was the only PT boat ever rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. There were even whispers of a possible court-martial on grounds of dereliction of duty.

Enter Joseph P. Kennedy, Jack's dad.

Joe was one of the richest blokes in America and a pioneer in the Art of the Spin--former bootlegger, stock manipulator, and Hollywood producer. It was Joe's dream to put a son in the White House, and to that end he

unleashed a juggernaut of publicity designed to sell his oldest surviving son to the American public.

Joe persuaded Pulitzer-winning author John Hersey, a Kennedy-confidant (his wife was Jack's ex-steady) to write an article for the New Yorker focusing on his son's efforts to lead the stranded PT-crew to safety. The resulting article portrayed Jack as the Dashing Naval Hero, Leader of Men.

When Jack ran for Congress in 1947--his first-ever campaign--the elder Kennedy circulated 150,000 copies of Hersey's story to Massachusetts voters. The returning WWII hero was elected with ease. Four years later, Jack was elected to the Senate. And in 1960..well, you know the rest.

The search for JFK

Joe Kennedy's behind-the-scenes machinations may have succeeded in putting a son in the Oval Office, but the elder Kennedy wasn't done spinning the PT 109 legend just yet.

In 1961, Joe successfully pitched the idea for a feature film based on his son's WWII-exploits to pal Jack Warner of Warner Brothers Studios. Joe handled contract negotiations himself, receiving approval over both script and selection of the actor to portray JFK.

Warner Brothers immediately began testing dozens of actors for the part of young Kennedy, including Peter Fonda, Roger Smith, Chad Everett--even Edd "Kookie" Byrnes (of 77 Sunset Strip fame) was considered. JFK himself favored Warren Beatty--who turned down the part.

Hollywood buzzed with conjecture: Which lucky leading man would snare the part of young Kennedy? Cliff Robertson would later recall his shock at being summoned to the Warners lot for a screen test. In his wildest dreams, he told a reporter, he never put himself in the mix.

No wonder: Robertson was 37-years-old and possessed none of the Kennedy charisma. Nonetheless, two days after testing he received a phone call from a friend in New York. "There's a picture of you and President Kennedy on the front page of the New York Times," the actor was told. "You've got the part."

Unbeknownst to Robertson, Warner Brothers had shipped each of the actors' tests to Paul Fischer, White House projectionist, who played them for Kennedy and his brother-in-law Peter Lawford. Kennedy selected Robertson.

Within weeks, Robertson received an invitation to 600 Pennsylvania Avenue. During their 45-minute confab, JFK made two requests. First, he asked the actor to switch the part in his hair from left to right. Then he told Robertson to forget the Boston accent, to play the part, in JFK's words, "non-regional," fearful that any actor attempting his veddy proper Hah-vahd inflection risked sounding ridiculous. To drive home the point, Kennedy actually performed a brief impersonation of a bad nightclub comic impersonating him--"Ahhsk not what yo-ah country can do for you." Robertson apparently got the message. As a parting gift, JFK gave Robertson a PT 109 tie clasp.

Next, Team Kennedy turned its attention to selecting a director. Warner's original choice, Raoul Walsh, was a once-great director whose 1928 film Regeneration had starred Gloria Swanson, Joe Kennedy's long-time mistress. But Walsh hadn't made a decent picture in years--decades, actually.

JFK's Press Secretary Pierre Salinger was skeptical, and asked Warner to send Walsh's most recent picture--the hokey Let's Go Marines--to the White House for screening. On the afternoon of Feb. 23, 1962, JFK took a seat in the projection room alongside Salinger. Ten minutes into the film, JFK had seen enough. He leaned over and whispered in Salinger's ear. Salinger stood, waved his arms, and shouted to Fischer to stop the film.

According to witnesses, Kennedy then turned to Salinger and said, "Tell Jack Warner to go f*ck himself."

Kennedy ultimately agreed to the selection of Lewis Milestone, who was replaced mere weeks into the film by Les Martinson (see David Whorf interview).

Florida shipyards from Panama City to Miami began converting Air Force rescue vessels into PT boats, which had long since become obsolete. In waters east of Panama City, one fleet of faux-PTs--suspected of being a Cuban flotilla--was stopped and searched by the US Coast Guard.

Island scenes were shot at Munson Island off Key West, and at Little Palm Island, an ultra-private, exclusive retreat half-way between Marathon and Key West. There was no electricity on Little Palm, so Joe Kennedy persuaded the state of Florida to install 3.5 miles of utility poles for the shoot.

The film, budgeted at $5 million, was completed in 11 weeks.

The view from Camelot

The President and First Lady screened PT 109 for the first time on Jan. 29, 1963, in the White House projection room. The next day JFK watched it again along with 35 White House staff members. According to Fischer's records, brothers Ted and Bobby watched the film on May 20, 1963; two days later the president's children, John-John, 3, and Caroline, 6, were shown the film as well.

The movie premiered on July 3, 1963, at the posh Beverly Hills Hilton, the first major motion picture premiere not held in a theater. This was, after all, a $100-a-ticket, black-tie gala to raise money for the Joseph P.Kennedy Child Care Center in Santa Monica. JFK did not attend. In his stead: Mother Rose Kennedy, sisters Pat Lawford (and husband Peter) and Eunice Shriver (and husband Sargent). "Biggest cheer of the evening," reported Newsweek, "came not during the picture but at a preceeding dinner when 100 waiters marched in bearing ice-cream cakes topped with gunmetal-gray plastic models of PT 109."

The film opened to less than sterling reviews. The New York Times called Robertson's performance "pious, pompous, and self-righteously smug," and dismissed the story as "synthetic and without the feel of truth." Newsweek's review, entitled "Jack the Skipper," offered: "Robertson doesn't look, act, or talk like (Kennedy)--still, one must believe as with Santa Claus."

PT 109 was only a moderate box office draw. It was, after all, a novelty: The first film ever made about a living president--and an enormously popular one, at that. The film abruptly ended its run in November of 1963; Warner Brothers yanked the film following Kennedy's assassination on November 22.

"I had hoped (PT 109) would be something of a classic," the late George Stevens (a Kennedy family-friend and director of Giant, Shane, and A Place in the Sun, among others) told reporters in 1974. "But it was not a very exceptional one." The Kennedys liked the film a great deal, Stevens recalled, and that was important in the end.

Ultimately, it was Jack Kennedy--the master ironist--who cut through the fog of myth and publicity created by his father, Spinmeister Joe.

Once, when asked how he managed to become a naval hero, JFK replied: "It was easy. They sunk my boat."

--Ken Brooks , Cult Movies magazine, Issue 41

Les Martinson (director)

Specialized in low budget, B-productions, from The Atomic Kid (1954, starring Mickey Rooney), to the campy Batman (1966). Eventually moved to TV, where his many directorial credits include Rescue From Gilligan's Island (1978).

Bryan Foy (producer)

Secured a place in film history by directing Warner's first talkie, Lights of New York (1928). Thereafter became known as "Keeper of the B's" for turning out scores of low-budget films. In 1953, as head of Warners' "B" division, Foy produced House of Wax, one of the most successful and popular 3-D flicks of all-time.

Cliff Robertson (JFK)

Son of a wealthy California rancher. Served in Merchant Marines during WWII, arriving in the Solomon Islands in August 1943--about the time Kennedy's PT sank. Appeared in Season One, Episode One of TV's Outer Limits, as well as two Twilight Zones. Directed opening and closing sequences of PT 109. Won the Oscar in 1968 for portrayal of a mentally-challenged adult-turned-genius in Charly. Over 40 films to his credit;appeared most recently in Spiderman (2002).

ALSO FEATURING: Ty Hardin (Ensign Leonard Thom)

Born Oscar Whipple Hungerford. Played football at Texas A&M under legendary coach Bear Bryant. Made film debut in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). Starred in TV western Bronco (1958-1962). Roles dwindled; moved to Spain and opened chain of laundromats while appearing in spaghetti-westerns. Expelled from Spain following drug bust; returned to US and lived as survivalist in Arizona before becoming a traveling evangelist.

The inside story of the making of that picture, PT 109--America's first marriage of presidential politics and Hollywood film-making--illustrates the principle that in Washington as in Tinseltown, it's all about the Art of the Spin.

The meteoric political rise of John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy--the protagonist of our tale--in fact began with a shamefaced debacle aboard patrol-torpedo boat 109 in the South Pacific during World War II. Kennedy was a 26-year-old Navy lieutenant in charge of the fast-moving, 80-foot PT boat, one of over 600 such vessels defending the South Pacific. In the moonless midnight blackness of August 1, 1943, Kennedy's 109 was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. Two of 12 crew members drowned; Kennedy led the survivors to safety, swimming island to island until help arrived.

The incident left Jack Kennedy deeply ashamed. He should have been: In the entire history of World War II, the 109 was the only PT boat ever rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. There were even whispers of a possible court-martial on grounds of dereliction of duty.

Enter Joseph P. Kennedy, Jack's dad.

Joe was one of the richest blokes in America and a pioneer in the Art of the Spin--former bootlegger, stock manipulator, and Hollywood producer. It was Joe's dream to put a son in the White House, and to that end he

unleashed a juggernaut of publicity designed to sell his oldest surviving son to the American public.

Joe persuaded Pulitzer-winning author John Hersey, a Kennedy-confidant (his wife was Jack's ex-steady) to write an article for the New Yorker focusing on his son's efforts to lead the stranded PT-crew to safety. The resulting article portrayed Jack as the Dashing Naval Hero, Leader of Men.

When Jack ran for Congress in 1947--his first-ever campaign--the elder Kennedy circulated 150,000 copies of Hersey's story to Massachusetts voters. The returning WWII hero was elected with ease. Four years later, Jack was elected to the Senate. And in 1960..well, you know the rest.

The search for JFK

Joe Kennedy's behind-the-scenes machinations may have succeeded in putting a son in the Oval Office, but the elder Kennedy wasn't done spinning the PT 109 legend just yet.

In 1961, Joe successfully pitched the idea for a feature film based on his son's WWII-exploits to pal Jack Warner of Warner Brothers Studios. Joe handled contract negotiations himself, receiving approval over both script and selection of the actor to portray JFK.

Warner Brothers immediately began testing dozens of actors for the part of young Kennedy, including Peter Fonda, Roger Smith, Chad Everett--even Edd "Kookie" Byrnes (of 77 Sunset Strip fame) was considered. JFK himself favored Warren Beatty--who turned down the part.

Hollywood buzzed with conjecture: Which lucky leading man would snare the part of young Kennedy? Cliff Robertson would later recall his shock at being summoned to the Warners lot for a screen test. In his wildest dreams, he told a reporter, he never put himself in the mix.

No wonder: Robertson was 37-years-old and possessed none of the Kennedy charisma. Nonetheless, two days after testing he received a phone call from a friend in New York. "There's a picture of you and President Kennedy on the front page of the New York Times," the actor was told. "You've got the part."

Unbeknownst to Robertson, Warner Brothers had shipped each of the actors' tests to Paul Fischer, White House projectionist, who played them for Kennedy and his brother-in-law Peter Lawford. Kennedy selected Robertson.

Within weeks, Robertson received an invitation to 600 Pennsylvania Avenue. During their 45-minute confab, JFK made two requests. First, he asked the actor to switch the part in his hair from left to right. Then he told Robertson to forget the Boston accent, to play the part, in JFK's words, "non-regional," fearful that any actor attempting his veddy proper Hah-vahd inflection risked sounding ridiculous. To drive home the point, Kennedy actually performed a brief impersonation of a bad nightclub comic impersonating him--"Ahhsk not what yo-ah country can do for you." Robertson apparently got the message. As a parting gift, JFK gave Robertson a PT 109 tie clasp.

Next, Team Kennedy turned its attention to selecting a director. Warner's original choice, Raoul Walsh, was a once-great director whose 1928 film Regeneration had starred Gloria Swanson, Joe Kennedy's long-time mistress. But Walsh hadn't made a decent picture in years--decades, actually.

JFK's Press Secretary Pierre Salinger was skeptical, and asked Warner to send Walsh's most recent picture--the hokey Let's Go Marines--to the White House for screening. On the afternoon of Feb. 23, 1962, JFK took a seat in the projection room alongside Salinger. Ten minutes into the film, JFK had seen enough. He leaned over and whispered in Salinger's ear. Salinger stood, waved his arms, and shouted to Fischer to stop the film.

According to witnesses, Kennedy then turned to Salinger and said, "Tell Jack Warner to go f*ck himself."

Kennedy ultimately agreed to the selection of Lewis Milestone, who was replaced mere weeks into the film by Les Martinson (see David Whorf interview).

Florida shipyards from Panama City to Miami began converting Air Force rescue vessels into PT boats, which had long since become obsolete. In waters east of Panama City, one fleet of faux-PTs--suspected of being a Cuban flotilla--was stopped and searched by the US Coast Guard.

Island scenes were shot at Munson Island off Key West, and at Little Palm Island, an ultra-private, exclusive retreat half-way between Marathon and Key West. There was no electricity on Little Palm, so Joe Kennedy persuaded the state of Florida to install 3.5 miles of utility poles for the shoot.

The film, budgeted at $5 million, was completed in 11 weeks.

The view from Camelot

The President and First Lady screened PT 109 for the first time on Jan. 29, 1963, in the White House projection room. The next day JFK watched it again along with 35 White House staff members. According to Fischer's records, brothers Ted and Bobby watched the film on May 20, 1963; two days later the president's children, John-John, 3, and Caroline, 6, were shown the film as well.

The movie premiered on July 3, 1963, at the posh Beverly Hills Hilton, the first major motion picture premiere not held in a theater. This was, after all, a $100-a-ticket, black-tie gala to raise money for the Joseph P.Kennedy Child Care Center in Santa Monica. JFK did not attend. In his stead: Mother Rose Kennedy, sisters Pat Lawford (and husband Peter) and Eunice Shriver (and husband Sargent). "Biggest cheer of the evening," reported Newsweek, "came not during the picture but at a preceeding dinner when 100 waiters marched in bearing ice-cream cakes topped with gunmetal-gray plastic models of PT 109."

The film opened to less than sterling reviews. The New York Times called Robertson's performance "pious, pompous, and self-righteously smug," and dismissed the story as "synthetic and without the feel of truth." Newsweek's review, entitled "Jack the Skipper," offered: "Robertson doesn't look, act, or talk like (Kennedy)--still, one must believe as with Santa Claus."

PT 109 was only a moderate box office draw. It was, after all, a novelty: The first film ever made about a living president--and an enormously popular one, at that. The film abruptly ended its run in November of 1963; Warner Brothers yanked the film following Kennedy's assassination on November 22.

"I had hoped (PT 109) would be something of a classic," the late George Stevens (a Kennedy family-friend and director of Giant, Shane, and A Place in the Sun, among others) told reporters in 1974. "But it was not a very exceptional one." The Kennedys liked the film a great deal, Stevens recalled, and that was important in the end.

Ultimately, it was Jack Kennedy--the master ironist--who cut through the fog of myth and publicity created by his father, Spinmeister Joe.

Once, when asked how he managed to become a naval hero, JFK replied: "It was easy. They sunk my boat."

--Ken Brooks , Cult Movies magazine, Issue 41

* *

PT 109 cast and crew...

Les Martinson (director)

Specialized in low budget, B-productions, from The Atomic Kid (1954, starring Mickey Rooney), to the campy Batman (1966). Eventually moved to TV, where his many directorial credits include Rescue From Gilligan's Island (1978).

Bryan Foy (producer)

Secured a place in film history by directing Warner's first talkie, Lights of New York (1928). Thereafter became known as "Keeper of the B's" for turning out scores of low-budget films. In 1953, as head of Warners' "B" division, Foy produced House of Wax, one of the most successful and popular 3-D flicks of all-time.

Cliff Robertson (JFK)

Son of a wealthy California rancher. Served in Merchant Marines during WWII, arriving in the Solomon Islands in August 1943--about the time Kennedy's PT sank. Appeared in Season One, Episode One of TV's Outer Limits, as well as two Twilight Zones. Directed opening and closing sequences of PT 109. Won the Oscar in 1968 for portrayal of a mentally-challenged adult-turned-genius in Charly. Over 40 films to his credit;appeared most recently in Spiderman (2002).

ALSO FEATURING: Ty Hardin (Ensign Leonard Thom)

Born Oscar Whipple Hungerford. Played football at Texas A&M under legendary coach Bear Bryant. Made film debut in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). Starred in TV western Bronco (1958-1962). Roles dwindled; moved to Spain and opened chain of laundromats while appearing in spaghetti-westerns. Expelled from Spain following drug bust; returned to US and lived as survivalist in Arizona before becoming a traveling evangelist.

INTERVIEW: David Whorf, PT 109 cast member...

David Whorf was a 28-year-old up-and-coming actor when he won the role of Seaman First-class Raymond Albert in PT 109. Whorf is the son of Richard Whorf, whose Hollywood directorial credits include Til the Clouds Roll By, a musical bio of Jerome Kern starring Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra (1946), and Champagne for Caesar, a wonderful, much-overlooked spoof of TV quiz shows, starring Ronald Coleman and Celeste Holm (1950). Recently, I talked with David Whorf about his role in PT 109 and his career as both actor and assistant director.

KB: How did you become involved with PT 109?

DW: Warner Brothers had a number of second-generation kids working on the film. Supreme Court Justice William Douglas' son William, Jr. played Gerald Zinser, one of the PT-crew members, and Bob Hope's son Tony worked in production. I was at an age where I was just right for the part of Raymond Albert. Still, I auditioned just like any other actor.

KB: What do you remember about the filming?

DW: We were out on the water in these air-sea rescue boats converted to look like PT's. A number of times during the shoot we saw Cubans floating from Cuba to Florida in the middle of the ocean--on inner tubes, boxes, anything that could float. They would try to give themselves up to us. We kept saying: "No, no--we're just making a movie. We're not the real Navy!" We shot on location at Munson Key. Warner Brothers arrived months in advance and built a large set that covered the island so that various sides of it could pass for different islands. As soon as we finished shooting, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened, so the locations we had used just days before were suddenly filled with rocket launchers and such.

KB: Leslie Martinson wasn't the original director, was he?

DW: No. Lewis Milestone was the original director. In fact, most of the actors signed on because of Milestone. The man was a true titan of the industry--he'd won an Academy Award with All Quiet on the Western Front, one of the all-time great films, and we all felt dearly towards him. But he was an older man and from time to time he'd take a snooze in his chair--never during a scene, mind you. But Byran Foy, the producer, didn't think he was up to the task. It was a shame because Milestone was all class. But Foy had him replaced.

When Martinson came aboard it was a stacked deck against him--as it would have been for anyone at that point, because we all felt loyalty to Milestone. Martinson was a trip. There's a scene near the end of the movie where Kennedy returns to the island aboard a boat to rescue his men. He shoots his rifle as a signal and we all come tumbling out of the jungle and swim towards the boat. Martinson was up on the boat with a loudspeaker, trying to create a mood, screaming: "You are the children of Isreal! You are being delivered, you children of Isreal!" We looked at each other and rolled our eyes--it was hard to keep from cracking up. We were like, "Why doesn't he just shut up and let us do the scene?"

KB: Did anyone from the White House attend the shooting?

DW: I never saw any official White House people. But we met the actual surviving crew members, all of whom came to Florida and spent time on the set. President Kennedy never came down--that disappointed me.

KB: The credits read: "Under the personal supervision of Jack Warner." Did Warner ever visit the set?

DW: No. He may have had an influence in the making of the film, but those shannanigans happen a million miles from the actors on the set.

KB: Perhaps the most powerful performances in the film involve your character, Raymond Albert.

DW: My scenes kind of evolved. The writers said, "We're looking for something we don't have yet"--they wanted some raw emotion, I guess. But they didn't have much freedom with the characters, except for the one I played. I was lucky in one respect: The character I was portraying--Raymond Albert--did not survive the war, so they had some freedom to be creative with him.

The scene on the island, where I smash the lantern in a fit of rage, was not that difficult to prepare for. But the apology scene (in which Albert apologizes to JFK, post-rescue, for angrily doubting him)...well, they wanted me to cry. Try though I might, I wasn't able to get a tear out. So I opted instead for shame, embarrassment, and anger at myself. I worked on those emotions--and I'd have to say it seemed to come across effectively.

It was tough to prepare for that scene. That day I tried to keep away from the idle chit-chat of the rest of the cast and concentrated on getting into a dark mood, working myself into a real downer trip--down, down, down. Then, when it was time to shoot, the trick was to avoid letting all the distractions on the set--the hammers, the grips, the electricians--get in the way of maintaining my focus. I'd say my scenes turned out favorably and I was very pleased with my performance.

KB: What about the rest of the cast?

DW: It was a great cast except for Ty Hardin. The man was a loose cannon, a real coo-coo. We used to refer to him as Try Harder. There was one scene he just couldn't get straight. He kept forgetting that we were fighting the Japanese, not the Indians. He was on the boat saying: "Yep, we're gonna get those Indians..." Martinson would yell, "CUT! Ty--we're fighting the Japanese." Ty wound up making the same mistake about seven times. The rest of us stood around just rolling our eyes.

KB: What was Robert Blake like at that point in his career?

DW: He hated to be called Bobby or Bob--it had to be Robert. And he hated for anyone to know he'd been Little Beaver (the Indian sidekick in 1940s serial Red Ryder). Blake was always an angry guy. I didn't know the source of his anger, but I sensed a dark side--everyone did. He carried a fistful of explosive, deep-seated angst around with him, but he used it to good effect his whole career.

He and I hit it off right away and got along great, which was a strange-bedfellows situation because we were so different. We actually became good friends, and Robert and his first wife Sondra and I socialized regularly for about six months after wrapping PT 109. Then we drifted our separate ways. His current dilemma is shocking and I frankly don't know what to think.

KB: What did you think of Robertson's performance as JFK?

DW: It was a bit reserved, but I think Robertson must have felt like he was walking a tightrope. He was portraying a standing president--something that had never been done before--and I don't think he wanted to insult the president in any way. I thought generally Cliff did a good job. He was lovely to work for. I still admire the man.

KB: Did you attend the premiere?

DW: No. That was a black-tie gala for biggies. But let me tell you about the first time I saw the film in a theater with a live audience. We have this sequence in the film where Kennedy is rescuing Marines off one of the island beaches. We see that Kennedy's PT-boat has lost gas and is drifting towards the shore and the Japanese are running to the edge of the beach with their mortars and machine guns. The boat is going to drift right into them and get shot to pieces. The film cuts back and forth: The guys are sweating. The boat is drifting. The Japs are coming. Well, sitting behind me in the theater was a young boy, couldn't have been more than nine or ten. He turned to his father and said, "Gee, Dad--why don't they just drop an anchor?" I laughed so hard I choked, and I've never been able to watch that sequence again without laughing. I mean, it was so stupid that we didn't think of that. Out of the mouths of babes!

KB: Were you happy with the response to PT 109?

DW: The movie was only a moderate success. What has been terrific is that the film still plays somewhere on cable several times every year. It has attained almost legend-like status over the years because of its association with the Kennedys. Of course, at this point, my annual residuals are down to about $4.53.

KB: Tell us about your other film appearances.

DW: My first motion picture was On Our Merry Way. This was around 1945 and I was eleven years old. A family friend, an actor and producer, requested me for the part of Sniffles Duggan. I read and they said,"He's terrific." But by the time the movie was released in '48 my voice had changed. When I saw the film I was so embarrased I wanted to hide behind the theater seat. I thought: "My lord, is that my squeaky little voice?" My shoot only lasted two weeks so I didn't really interact with Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda. I had some scenes with Fred McMurray, though, which was interesting because later in my Dad's career he directed Fred in My Three Sons.

In the 1960s I appeared in One Way Wahini, but you'll have to forgive me for that one. The only thing good about it was the free trip to Hawaii--and I was able to afford a new car afterwards. Then I made Twist All Night, which was one of those B-movie nine-day wonders, made during the twist craze. Louis Prima was fun. But the movie? Bad. Bad. Bad.

So I worked as a 2nd Assistant Director and continued my acting career, bit parts here and there--a Hazel, a Dr. Kildare. But it was frustrating. As a young actor, I'd fight real hard for a part and then get on the set and sit around for five or six hours until they'd get to me. By that time my energy was gone. I liked the theater much better, so I spent a lot of time in the theatre, in summer stock, in both New England and Denver. I enjoyed that tremendously.

KB: What was it like on the set of Caddyshack?

DW: I was First Assistant director. Actually, I replaced somebody and had one day to prep and get ready. I figured I could handle it, but the cocaine was flying all over the place--the set was a zoo. And the movie that came out had nothing at all to do with the movie we shot. Bill Murray didn't show up until we were about three-fourths of the way through. He came down for four days and changed the whole thing, made stuff up, basically winged it. The gopher wasn't even in the movie I shot. When I finally saw the film I was like, "What movie is this?"

Caddyshack was Harold Ramis' first directing job, and he was a bit lost at times. I told him, "Just listen to your First Assistant Director--he'll tell you what to do." Turns out there's some really funny stuff in there, so it worked out fine.

KB: What is an assistant director's role?

DW: First assistant director is like the foreman--you run the set. You gather information from the various departments, set the shooting schedule, and--just like a stage manager in theater or television--keep everything rolling. The assistant director tells everyone involved what to do, when to do it, and where to go.

KB: Are you currently involved in any projects?

DW: I haven't done anything in a couple of years, mostly because everybody I used to work with is dead. The last thing I did was the first season of CSI as assistant director. I'd hoped to get some directing jobs out of it, but at my age--I'll be 70 soon--it would require too much traveling and time away from home. For years I worked as assistant director for Larry Pierce on shows like Batman and Cannon, and it was terrific to feel such mutual respect and fun and laughter while we were working. That doesn't seem to happen much anymore, and I miss that.

KB: Tell us about your father, Robert Whorf.

DW: Dad started on stage in New York with the Theater Guild working with Lynn Fontaine and Alfred Lunt, and was involved in the Pulitzer Prize winning plays of the 1930s. In the late '30s, Dad was brought to Hollywood to appear in Keeper of the Flame with Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. We moved to Hollywood for good in May 1941 when Dad appeared in Warner Brothers' Blues in the Night. He continued his acting career during the war years but gradually turned to directing. He was a man of tremendous talent: as an actor, director, painter, sculptor, costume designer. Dad was a hard act to follow.

KB: We appreciate your time, Mr. Whorf.

DW: Let me tell you one last PT 109 story. The late Sammy Reese played one of the PT-crewmen, and he and I became friends. Sammy told me he had written to President Kennedy and had gotten an autographed picture. I said, "Oh my gosh, I'd love to have one of those." So I wrote Kennedy a letter.

Of course, on Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, Kennedy was shot. The next day when the postman arrived I noticed his hands were shaking. He was holding an envelope marked The White House. Inside was a letter of thanks from Kennedy's secretary Evelyn Lincoln. Then I pulled out the photo. It was signed, "Warmest regards, Jack Kennedy."

--Ken Brooks

Cult Movies magazine, Issue 41

KB: How did you become involved with PT 109?

DW: Warner Brothers had a number of second-generation kids working on the film. Supreme Court Justice William Douglas' son William, Jr. played Gerald Zinser, one of the PT-crew members, and Bob Hope's son Tony worked in production. I was at an age where I was just right for the part of Raymond Albert. Still, I auditioned just like any other actor.

KB: What do you remember about the filming?

DW: We were out on the water in these air-sea rescue boats converted to look like PT's. A number of times during the shoot we saw Cubans floating from Cuba to Florida in the middle of the ocean--on inner tubes, boxes, anything that could float. They would try to give themselves up to us. We kept saying: "No, no--we're just making a movie. We're not the real Navy!" We shot on location at Munson Key. Warner Brothers arrived months in advance and built a large set that covered the island so that various sides of it could pass for different islands. As soon as we finished shooting, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened, so the locations we had used just days before were suddenly filled with rocket launchers and such.

KB: Leslie Martinson wasn't the original director, was he?

DW: No. Lewis Milestone was the original director. In fact, most of the actors signed on because of Milestone. The man was a true titan of the industry--he'd won an Academy Award with All Quiet on the Western Front, one of the all-time great films, and we all felt dearly towards him. But he was an older man and from time to time he'd take a snooze in his chair--never during a scene, mind you. But Byran Foy, the producer, didn't think he was up to the task. It was a shame because Milestone was all class. But Foy had him replaced.

When Martinson came aboard it was a stacked deck against him--as it would have been for anyone at that point, because we all felt loyalty to Milestone. Martinson was a trip. There's a scene near the end of the movie where Kennedy returns to the island aboard a boat to rescue his men. He shoots his rifle as a signal and we all come tumbling out of the jungle and swim towards the boat. Martinson was up on the boat with a loudspeaker, trying to create a mood, screaming: "You are the children of Isreal! You are being delivered, you children of Isreal!" We looked at each other and rolled our eyes--it was hard to keep from cracking up. We were like, "Why doesn't he just shut up and let us do the scene?"

KB: Did anyone from the White House attend the shooting?

DW: I never saw any official White House people. But we met the actual surviving crew members, all of whom came to Florida and spent time on the set. President Kennedy never came down--that disappointed me.

KB: The credits read: "Under the personal supervision of Jack Warner." Did Warner ever visit the set?

DW: No. He may have had an influence in the making of the film, but those shannanigans happen a million miles from the actors on the set.

KB: Perhaps the most powerful performances in the film involve your character, Raymond Albert.

DW: My scenes kind of evolved. The writers said, "We're looking for something we don't have yet"--they wanted some raw emotion, I guess. But they didn't have much freedom with the characters, except for the one I played. I was lucky in one respect: The character I was portraying--Raymond Albert--did not survive the war, so they had some freedom to be creative with him.

The scene on the island, where I smash the lantern in a fit of rage, was not that difficult to prepare for. But the apology scene (in which Albert apologizes to JFK, post-rescue, for angrily doubting him)...well, they wanted me to cry. Try though I might, I wasn't able to get a tear out. So I opted instead for shame, embarrassment, and anger at myself. I worked on those emotions--and I'd have to say it seemed to come across effectively.

It was tough to prepare for that scene. That day I tried to keep away from the idle chit-chat of the rest of the cast and concentrated on getting into a dark mood, working myself into a real downer trip--down, down, down. Then, when it was time to shoot, the trick was to avoid letting all the distractions on the set--the hammers, the grips, the electricians--get in the way of maintaining my focus. I'd say my scenes turned out favorably and I was very pleased with my performance.

KB: What about the rest of the cast?

DW: It was a great cast except for Ty Hardin. The man was a loose cannon, a real coo-coo. We used to refer to him as Try Harder. There was one scene he just couldn't get straight. He kept forgetting that we were fighting the Japanese, not the Indians. He was on the boat saying: "Yep, we're gonna get those Indians..." Martinson would yell, "CUT! Ty--we're fighting the Japanese." Ty wound up making the same mistake about seven times. The rest of us stood around just rolling our eyes.

KB: What was Robert Blake like at that point in his career?

DW: He hated to be called Bobby or Bob--it had to be Robert. And he hated for anyone to know he'd been Little Beaver (the Indian sidekick in 1940s serial Red Ryder). Blake was always an angry guy. I didn't know the source of his anger, but I sensed a dark side--everyone did. He carried a fistful of explosive, deep-seated angst around with him, but he used it to good effect his whole career.

He and I hit it off right away and got along great, which was a strange-bedfellows situation because we were so different. We actually became good friends, and Robert and his first wife Sondra and I socialized regularly for about six months after wrapping PT 109. Then we drifted our separate ways. His current dilemma is shocking and I frankly don't know what to think.

KB: What did you think of Robertson's performance as JFK?

DW: It was a bit reserved, but I think Robertson must have felt like he was walking a tightrope. He was portraying a standing president--something that had never been done before--and I don't think he wanted to insult the president in any way. I thought generally Cliff did a good job. He was lovely to work for. I still admire the man.

KB: Did you attend the premiere?

DW: No. That was a black-tie gala for biggies. But let me tell you about the first time I saw the film in a theater with a live audience. We have this sequence in the film where Kennedy is rescuing Marines off one of the island beaches. We see that Kennedy's PT-boat has lost gas and is drifting towards the shore and the Japanese are running to the edge of the beach with their mortars and machine guns. The boat is going to drift right into them and get shot to pieces. The film cuts back and forth: The guys are sweating. The boat is drifting. The Japs are coming. Well, sitting behind me in the theater was a young boy, couldn't have been more than nine or ten. He turned to his father and said, "Gee, Dad--why don't they just drop an anchor?" I laughed so hard I choked, and I've never been able to watch that sequence again without laughing. I mean, it was so stupid that we didn't think of that. Out of the mouths of babes!

KB: Were you happy with the response to PT 109?

DW: The movie was only a moderate success. What has been terrific is that the film still plays somewhere on cable several times every year. It has attained almost legend-like status over the years because of its association with the Kennedys. Of course, at this point, my annual residuals are down to about $4.53.

KB: Tell us about your other film appearances.

DW: My first motion picture was On Our Merry Way. This was around 1945 and I was eleven years old. A family friend, an actor and producer, requested me for the part of Sniffles Duggan. I read and they said,"He's terrific." But by the time the movie was released in '48 my voice had changed. When I saw the film I was so embarrased I wanted to hide behind the theater seat. I thought: "My lord, is that my squeaky little voice?" My shoot only lasted two weeks so I didn't really interact with Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda. I had some scenes with Fred McMurray, though, which was interesting because later in my Dad's career he directed Fred in My Three Sons.

In the 1960s I appeared in One Way Wahini, but you'll have to forgive me for that one. The only thing good about it was the free trip to Hawaii--and I was able to afford a new car afterwards. Then I made Twist All Night, which was one of those B-movie nine-day wonders, made during the twist craze. Louis Prima was fun. But the movie? Bad. Bad. Bad.

So I worked as a 2nd Assistant Director and continued my acting career, bit parts here and there--a Hazel, a Dr. Kildare. But it was frustrating. As a young actor, I'd fight real hard for a part and then get on the set and sit around for five or six hours until they'd get to me. By that time my energy was gone. I liked the theater much better, so I spent a lot of time in the theatre, in summer stock, in both New England and Denver. I enjoyed that tremendously.

KB: What was it like on the set of Caddyshack?

DW: I was First Assistant director. Actually, I replaced somebody and had one day to prep and get ready. I figured I could handle it, but the cocaine was flying all over the place--the set was a zoo. And the movie that came out had nothing at all to do with the movie we shot. Bill Murray didn't show up until we were about three-fourths of the way through. He came down for four days and changed the whole thing, made stuff up, basically winged it. The gopher wasn't even in the movie I shot. When I finally saw the film I was like, "What movie is this?"

Caddyshack was Harold Ramis' first directing job, and he was a bit lost at times. I told him, "Just listen to your First Assistant Director--he'll tell you what to do." Turns out there's some really funny stuff in there, so it worked out fine.

KB: What is an assistant director's role?

DW: First assistant director is like the foreman--you run the set. You gather information from the various departments, set the shooting schedule, and--just like a stage manager in theater or television--keep everything rolling. The assistant director tells everyone involved what to do, when to do it, and where to go.

KB: Are you currently involved in any projects?

DW: I haven't done anything in a couple of years, mostly because everybody I used to work with is dead. The last thing I did was the first season of CSI as assistant director. I'd hoped to get some directing jobs out of it, but at my age--I'll be 70 soon--it would require too much traveling and time away from home. For years I worked as assistant director for Larry Pierce on shows like Batman and Cannon, and it was terrific to feel such mutual respect and fun and laughter while we were working. That doesn't seem to happen much anymore, and I miss that.

KB: Tell us about your father, Robert Whorf.

DW: Dad started on stage in New York with the Theater Guild working with Lynn Fontaine and Alfred Lunt, and was involved in the Pulitzer Prize winning plays of the 1930s. In the late '30s, Dad was brought to Hollywood to appear in Keeper of the Flame with Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. We moved to Hollywood for good in May 1941 when Dad appeared in Warner Brothers' Blues in the Night. He continued his acting career during the war years but gradually turned to directing. He was a man of tremendous talent: as an actor, director, painter, sculptor, costume designer. Dad was a hard act to follow.

KB: We appreciate your time, Mr. Whorf.

DW: Let me tell you one last PT 109 story. The late Sammy Reese played one of the PT-crewmen, and he and I became friends. Sammy told me he had written to President Kennedy and had gotten an autographed picture. I said, "Oh my gosh, I'd love to have one of those." So I wrote Kennedy a letter.

Of course, on Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, Kennedy was shot. The next day when the postman arrived I noticed his hands were shaking. He was holding an envelope marked The White House. Inside was a letter of thanks from Kennedy's secretary Evelyn Lincoln. Then I pulled out the photo. It was signed, "Warmest regards, Jack Kennedy."

--Ken Brooks

Cult Movies magazine, Issue 41

Hugh Hefner's first flick: The Naked Ape...Hollywood's legendary lost movie

There she sat, on a stool not six feet from me, in the University of Florida infirmary: The delicious Victoria Principal, a 22-year-old vision from heaven--from Hollywood, actually--in a white, tight-clinging see-through blouse and mini-skirt.

Did I mention I was in my underwear?

It was the spring of 1972--my sophomore year at UF--and I was making my film debut, playing one of 20 army draftees (stripped to our skivvies) undergoing a pre-induction physical in The Naked Ape, a major motion picture being filmed on campus.

As we waited for the next scene, Ms. Principal crossed her legs and swept a wisp of hair from her eyes. When she finally spoke, her words etched indelibly into my id: "The camera is the perfect lover," she purred. "It gives to you exactly what you give to it." We swooned.

The director, Donald Driver--a wispy, wiry, nervous sort--called, "Places everyone," and reminded us once again of the Extra's Holy Commandment: "Whatever you do, DO NOT LOOK AT THE CAMERA!"

Then-- "Action!"

We took our places. As extras we were simply human scenery, of course. Every so often, Driver would catch one of us peering into the camera's eye. "Cut!" he'd bark, then chew out the offender--"the camera does not exist!" he'd howl--and we'd run through yet another take.

No one knew it at the time, but Driver's Naked Ape was destined to become one of Hollywood's legendary Lost Movies. After a short run following its 1973 release, the film mysteriously vanished; today, over a quarter-century later, it remains unseen. What happened?

From book to film

The movie version of the 1967 best-seller The Naked Ape was almost never filmed at all.

Desmond Morris' book had explored human patterns of sex and aggression, tracing them to our primal, simian roots. For years Morris had rejected offers to sell movie rights, convinced his quirky treatise--part textbook, part pop-anthropology--was unsuitable for filming.

Hollywood producer Zev Bufman thought otherwise. He flew to Morris' home on the Mediterranean isle of Malta and launched into his pitch. Morris interrupted. "Anyone who feels passionately enough to travel halfway around the world should have it," the author told him. "It's yours."

Bufman turned to Playboy magazine magnate Hugh Hefner for financing. A deal was struck: Playboy and Universal Pictures would split the film's $2 millon budget.

Signing Principal was a coup. The former Miss Miami's rise to Hollywood sex-goddess was swift: Her 1972 film debut was opposite Paul Newman in Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean. (Principal's Playboy contract granted her the lead in Naked Ape provided she would pose for one of the mag's naughty pictorials. A six-page spread displaying Principal's earthly delights appears in Playboy's Sept.'73 issue, timed to the release of the movie).

Next to sign was Johnny Crawford, former original mousekateer and child star of TV's late-1950s series The Rifleman, as Principal's love interest. For Naked Ape, Crawford would play a college student facing the draft and a stint in Viet Nam; Principal would play the babe in Crawford's "Sexual Behavior" class.

Big ape on campus

Months before shooting commenced, Bufman began searching for a campus location. He liked UF, he said, because of "its different types of architecture, as if it could be any college, in any part of the country." Bufman then mailed the screenplay to UF President Stephen O'Connell, who called the script "high caliber," and "worthy of filming at the university." In return, the state of Florida--eager to entice the Hollywood film industry--agreed to supply the production with limos and private planes.

Driver's 40-member production crew invaded campus on Monday, February 22. Ads were placed in the student-run newspaper, the Alligator: Auditions for extras would be held at the UF auditorium.

As it turned out, Driver was merely looking for warm bodies with enough sense not to stare into the camera lens. The selection process, in fact, appeared random. Volunteers lined the stage, and a nod from Driver meant you were "in." Nearly 200 students were selected at the princely salary of $15 a day.

Scenes were shot in the hub bookstore, infirmary, gymnasium, and classrooms at Peabody Hall. I was present when Crawford arrived for his first scene, shot outside the infirmary. When an extra complimented Crawford on his Hollywood-style lizard boots, the star looked stricken. His boots were totally out-of-character (de rigueur footwear on campus, '72: sneakers or sandals). "Who wears a size ten?" Crawford asked. There on the infirmary steps, Crawford whipped out a $20 bill and bought an extra's beat-up high-tops. Our jaws went slack. $20! To dorm-dwellers with pre-paid meal tickets, this was three month's living expenses. Welcome to big-time show-biz.

Campus filming took ten days. I was amazed to learn that Driver actually sat in a director's chair with his name across the back, and that "takes" actually began with a black-and-white slap-board. I paraded through the rest of my scenes with all the natural acting ability of a marionette.

A brief, flickering image

The movie, released in August 1973, was ignored by the nation's critics, most of whom didn't even bother to unsnap their typewriter covers. Among major dailies, only the Los Angeles Times bothered to publish a review:

"Based on the evidence before us," wrote Times critic Charles Champlin, "those who said that Desmond Morris' Naked Ape couldn't be made into a movie were right." Champlin called the film, "achingly tasteless." Hef's first foray into feature films was a bomb--a 500-pound daisy-cutter, in fact.

How bad was Naked Ape? This bad: Three decades after its release, the movie is still unavailable to the public in any format whatsoever. To his eternal humiliation, Hef created the counterculture equivalent of Plan Nine from Outer Space--but by god this turkey wasn't going to wind up as some late-night art-house laughing stock.

The movie hasn't been seen since 1974. By now one has to assume the reels are locked away in a closet at Hef's place, crumbling inexorably into neat piles of acetate dust.

Recently, I contacted a leading internet source dealing in hard-to-find movies and inquired about the obscure object of my desire. "Naked Ape seems to have fallen off the ends of the earth," he told me. "You can't even find a bootleg copy. It's the film collector's Holy Grail."

I saw the movie only once, in the fall of 1973. I had graduated that spring and moved back home to Panama City. I checked newspaper movie ads each day, until finally...

My first tip-off that Naked Ape had tanked big-time was this: It was shown at a local drive-in, second-billed to a motorcycle flick--a second-rate drive-in throw-away.

Ouch.

I felt a jolt of adrenaline nonetheless. I was officially a movie actor--appearing, I liked to add, alongside my voluptous Vicky. But wait a second. That final moment I'm on screen--did you notice? Oh geez! I'm looking right into the camera!

Did I mention I was in my underwear?

Did I mention I was in my underwear?

It was the spring of 1972--my sophomore year at UF--and I was making my film debut, playing one of 20 army draftees (stripped to our skivvies) undergoing a pre-induction physical in The Naked Ape, a major motion picture being filmed on campus.

As we waited for the next scene, Ms. Principal crossed her legs and swept a wisp of hair from her eyes. When she finally spoke, her words etched indelibly into my id: "The camera is the perfect lover," she purred. "It gives to you exactly what you give to it." We swooned.

The director, Donald Driver--a wispy, wiry, nervous sort--called, "Places everyone," and reminded us once again of the Extra's Holy Commandment: "Whatever you do, DO NOT LOOK AT THE CAMERA!"

Then-- "Action!"

We took our places. As extras we were simply human scenery, of course. Every so often, Driver would catch one of us peering into the camera's eye. "Cut!" he'd bark, then chew out the offender--"the camera does not exist!" he'd howl--and we'd run through yet another take.

No one knew it at the time, but Driver's Naked Ape was destined to become one of Hollywood's legendary Lost Movies. After a short run following its 1973 release, the film mysteriously vanished; today, over a quarter-century later, it remains unseen. What happened?

From book to film

The movie version of the 1967 best-seller The Naked Ape was almost never filmed at all.

Desmond Morris' book had explored human patterns of sex and aggression, tracing them to our primal, simian roots. For years Morris had rejected offers to sell movie rights, convinced his quirky treatise--part textbook, part pop-anthropology--was unsuitable for filming.

Hollywood producer Zev Bufman thought otherwise. He flew to Morris' home on the Mediterranean isle of Malta and launched into his pitch. Morris interrupted. "Anyone who feels passionately enough to travel halfway around the world should have it," the author told him. "It's yours."

Bufman turned to Playboy magazine magnate Hugh Hefner for financing. A deal was struck: Playboy and Universal Pictures would split the film's $2 millon budget.

Signing Principal was a coup. The former Miss Miami's rise to Hollywood sex-goddess was swift: Her 1972 film debut was opposite Paul Newman in Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean. (Principal's Playboy contract granted her the lead in Naked Ape provided she would pose for one of the mag's naughty pictorials. A six-page spread displaying Principal's earthly delights appears in Playboy's Sept.'73 issue, timed to the release of the movie).

Next to sign was Johnny Crawford, former original mousekateer and child star of TV's late-1950s series The Rifleman, as Principal's love interest. For Naked Ape, Crawford would play a college student facing the draft and a stint in Viet Nam; Principal would play the babe in Crawford's "Sexual Behavior" class.

Big ape on campus

Months before shooting commenced, Bufman began searching for a campus location. He liked UF, he said, because of "its different types of architecture, as if it could be any college, in any part of the country." Bufman then mailed the screenplay to UF President Stephen O'Connell, who called the script "high caliber," and "worthy of filming at the university." In return, the state of Florida--eager to entice the Hollywood film industry--agreed to supply the production with limos and private planes.

Driver's 40-member production crew invaded campus on Monday, February 22. Ads were placed in the student-run newspaper, the Alligator: Auditions for extras would be held at the UF auditorium.

As it turned out, Driver was merely looking for warm bodies with enough sense not to stare into the camera lens. The selection process, in fact, appeared random. Volunteers lined the stage, and a nod from Driver meant you were "in." Nearly 200 students were selected at the princely salary of $15 a day.

Scenes were shot in the hub bookstore, infirmary, gymnasium, and classrooms at Peabody Hall. I was present when Crawford arrived for his first scene, shot outside the infirmary. When an extra complimented Crawford on his Hollywood-style lizard boots, the star looked stricken. His boots were totally out-of-character (de rigueur footwear on campus, '72: sneakers or sandals). "Who wears a size ten?" Crawford asked. There on the infirmary steps, Crawford whipped out a $20 bill and bought an extra's beat-up high-tops. Our jaws went slack. $20! To dorm-dwellers with pre-paid meal tickets, this was three month's living expenses. Welcome to big-time show-biz.

Campus filming took ten days. I was amazed to learn that Driver actually sat in a director's chair with his name across the back, and that "takes" actually began with a black-and-white slap-board. I paraded through the rest of my scenes with all the natural acting ability of a marionette.

A brief, flickering image

The movie, released in August 1973, was ignored by the nation's critics, most of whom didn't even bother to unsnap their typewriter covers. Among major dailies, only the Los Angeles Times bothered to publish a review:

"Based on the evidence before us," wrote Times critic Charles Champlin, "those who said that Desmond Morris' Naked Ape couldn't be made into a movie were right." Champlin called the film, "achingly tasteless." Hef's first foray into feature films was a bomb--a 500-pound daisy-cutter, in fact.

How bad was Naked Ape? This bad: Three decades after its release, the movie is still unavailable to the public in any format whatsoever. To his eternal humiliation, Hef created the counterculture equivalent of Plan Nine from Outer Space--but by god this turkey wasn't going to wind up as some late-night art-house laughing stock.

The movie hasn't been seen since 1974. By now one has to assume the reels are locked away in a closet at Hef's place, crumbling inexorably into neat piles of acetate dust.

Recently, I contacted a leading internet source dealing in hard-to-find movies and inquired about the obscure object of my desire. "Naked Ape seems to have fallen off the ends of the earth," he told me. "You can't even find a bootleg copy. It's the film collector's Holy Grail."

I saw the movie only once, in the fall of 1973. I had graduated that spring and moved back home to Panama City. I checked newspaper movie ads each day, until finally...

My first tip-off that Naked Ape had tanked big-time was this: It was shown at a local drive-in, second-billed to a motorcycle flick--a second-rate drive-in throw-away.

Ouch.

I felt a jolt of adrenaline nonetheless. I was officially a movie actor--appearing, I liked to add, alongside my voluptous Vicky. But wait a second. That final moment I'm on screen--did you notice? Oh geez! I'm looking right into the camera!

Did I mention I was in my underwear?

--Ken Brooks, Cult Movies magazine, Issue 40

The Shocking Spring Break Scandal of 1929

This time--in the opinion of the Panama City newspaper --our visiting Spring Breakers had gone too, too far.

"Absolutely the most disgusting (display) we have ever seen," was one description from the editorial page. "Exceeds all bounds of good taste," was another. "Rotten and distasteful," was yet another.

So, you ask, what over-the-top spring break activity was the target of such editorial ire? Bikini contest? Barely-clad babes riding mechanical bulls? Foxy ladies using American flags as a bun warmers?

Uh, not exactly. You see, the above quotes are not from this year's Panama City News-Herald coverage of spring break.

They're from the Panama City Pilot, and the date is April 25, 1929--that's three-quarters-of-a-century ago!

Seems that the University of Florida baseball team, in town for a series of games at the local ballfield, was sponsoring a dance--fully chaperoned, by the way--in the crystal ballroom of the Dixie-Sherman Hotel in downtown Panama City.

A local band, the Jimmie Lee Orchestra, was on hand to--in the words of the Pilot--"render the jazz and beautiful waltzes...with all the pep and vim of old."

The paper reported: "Scores of girls from Florida State College for Women will arrive in the city Friday afternoon to attend the dances."

And that's when trouble started. Seems the UF students placed posters advertising their dance in store windows around town. It was these broadsides that inspired the above quotes.

"The offending posters," reported the Pilot, "describe the dance as a 'hop,' ...with "enough sorority girls from Tallahassee to stock all the harems in Turkey."

"This is scarcely complimentary to the young ladies to whom the reference is made," the Pilot said. "Apparently the University's instruction in the art and ethics of advertising is gleaned from the pages of Whiz-Bang Monthly."

That's right: the big controversy of Spring Break '29 was over the use of the word "harem," and all the shady connotations it whipped up in the minds of Pilot editors! It was a different world back then, wasn't it?

By the way...anyone know where I can find the April '29 issue of Whiz-Bang Monthly?

--Ken Brooks

Panama City News Herald, March 22, 2000

"Absolutely the most disgusting (display) we have ever seen," was one description from the editorial page. "Exceeds all bounds of good taste," was another. "Rotten and distasteful," was yet another.

So, you ask, what over-the-top spring break activity was the target of such editorial ire? Bikini contest? Barely-clad babes riding mechanical bulls? Foxy ladies using American flags as a bun warmers?

Uh, not exactly. You see, the above quotes are not from this year's Panama City News-Herald coverage of spring break.

They're from the Panama City Pilot, and the date is April 25, 1929--that's three-quarters-of-a-century ago!

Seems that the University of Florida baseball team, in town for a series of games at the local ballfield, was sponsoring a dance--fully chaperoned, by the way--in the crystal ballroom of the Dixie-Sherman Hotel in downtown Panama City.

A local band, the Jimmie Lee Orchestra, was on hand to--in the words of the Pilot--"render the jazz and beautiful waltzes...with all the pep and vim of old."

The paper reported: "Scores of girls from Florida State College for Women will arrive in the city Friday afternoon to attend the dances."

And that's when trouble started. Seems the UF students placed posters advertising their dance in store windows around town. It was these broadsides that inspired the above quotes.

"The offending posters," reported the Pilot, "describe the dance as a 'hop,' ...with "enough sorority girls from Tallahassee to stock all the harems in Turkey."

"This is scarcely complimentary to the young ladies to whom the reference is made," the Pilot said. "Apparently the University's instruction in the art and ethics of advertising is gleaned from the pages of Whiz-Bang Monthly."

That's right: the big controversy of Spring Break '29 was over the use of the word "harem," and all the shady connotations it whipped up in the minds of Pilot editors! It was a different world back then, wasn't it?

By the way...anyone know where I can find the April '29 issue of Whiz-Bang Monthly?

--Ken Brooks

Panama City News Herald, March 22, 2000

Four days before Dallas, JFK's last visit to Florida

We know the scene all too well. It's November 1963, and John F. Kennedy, 46, America's handsome, charismatic president, rides in an open limousine, waving to crowds as his motorcade winds through the city's downtown streets.

This time, however, no shots would ring out.

The date is Monday, November 18, four days before the president would be gunned down in Dallas. This day, Kennedy basks in Florida's adulation as his motorcade cruises through the streets of Tampa.