Thursday, May 29, 2008

Tampa's Plant Field, April 4, 1919: The spring training home run that changed baseball history...forever!

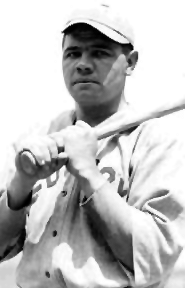

With one swing of the bat on an April afternoon in 1919 in Tampa, George Herman "Babe" Ruth changed the course of American sports history.

As pitcher for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, Ruth had emerged as the American League's premier left-hander, winning 78 games and leading his team to two World Series titles.

But Babe loved to hit and wanted to play every day. Team owner Harry Frazee disagreed.

When the team arrived in Tampa for spring training in March of 1919, Ruth wasn't among them, holding out for $15,000--an unheard of salary. And he wanted to play outfield, not pitch.

With the rest of the team in Tampa, Frazee and Ruth met in New York and came to terms: $10,000 a year for three years...but Ruth would stay on the mound. Babe signed, then caught the midnight train to Tampa.

He arrived in time for Boston's first exhibition game, on Friday, April 4 against the New York Giants, to be played at Plant Field, located on the site of the current McKay Auditorium at the University of Tampa. Bases had been laid out on the vast grounds of a racetrack.

At 4:15pm Friday, Billy Sunday, the nation's leading evangelist, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. (Sunday, himself a former big leaguer, was in town for a tent revival).

Ruth led off the bottom of the second. Giants pitcher George Smith hurled a fastball down the middle. Gripping the bat so far down the handle his right pinky actually hung off the butt-end, like a society matron sipping tea, the Babe swung and the ball rocketed toward right field. Giants outfielder Ross Youngs turned and ran, but halfway to the fence he stopped. The ball was still climbing. It bounced clear across the race track and rolled to a stop. A youngster retrieved the ball.

After the game, won by Boston 5 to 3, sportswriters asked Youngs to show them where Ruth's ball had come to rest. Laboriously, the writers paced the distance back to home plate.

The phrase "tape-measure shot" hadn't been invented yet, but it soon would be. The blast measured somewhere between 587 to 600 feet. Even Giants' manager John McGraw, a crusty old bird not given to hyperbole, called it "the longest ball I've ever seen hit."

It was the longest ball anyone could ever remember seeing hit. And by a pitcher! Later that evening, the ball--signed by Babe and Barrow--was presented to Billy Sunday at his tent.

Headlines in Saturday's Tampa Tribune screamed: "RUTH DRIVES GIANTS TO DEFEAT AND MAKES 'EM DRINK, TOO, B'GADS." The reporter, calling Ruth's homer a "wallop stupendous," wrote: "The Giants were still marveling last night. Many of them have never seen the Tarzan

perform since he annexed his slugging habits."

Monday, April 7, the Red Sox broke camp and headed north, barnstorming along the way with games in Gainesville, Winston-Salem, Charleston. In every town, huge crowds buzzed about mighty Babe and his blast. Frazee was becoming convinced: Babe needed to play every day.

During the 1919 season Babe pitched 17 games, but it was his final season on the mound. Playing outfield for Boston on days he didn't pitch, Ruth hit an astounding 29 home runs. That may not seem like much to today's fan. But consider: Before 1919, the single-season record for homers was 24, held by Gabby Cravath of the Philadelphia Phillies. In 1920, playing every day, Babe hit more homers (54) than any entire team in the American League! By the time he retired in 1935, Ruth had hit more homers than any man in the game's history.

Plant Stadium was razed in 2002 and replaced with a modern edifice, but a plaque on campus commemorates that historic swing of the bat on an April afternoon in Tampa, a swing that transformed the legend of Babe Ruth--and American sports--forever.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 18

As pitcher for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, Ruth had emerged as the American League's premier left-hander, winning 78 games and leading his team to two World Series titles.

But Babe loved to hit and wanted to play every day. Team owner Harry Frazee disagreed.

When the team arrived in Tampa for spring training in March of 1919, Ruth wasn't among them, holding out for $15,000--an unheard of salary. And he wanted to play outfield, not pitch.

With the rest of the team in Tampa, Frazee and Ruth met in New York and came to terms: $10,000 a year for three years...but Ruth would stay on the mound. Babe signed, then caught the midnight train to Tampa.

He arrived in time for Boston's first exhibition game, on Friday, April 4 against the New York Giants, to be played at Plant Field, located on the site of the current McKay Auditorium at the University of Tampa. Bases had been laid out on the vast grounds of a racetrack.

At 4:15pm Friday, Billy Sunday, the nation's leading evangelist, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. (Sunday, himself a former big leaguer, was in town for a tent revival).

Ruth led off the bottom of the second. Giants pitcher George Smith hurled a fastball down the middle. Gripping the bat so far down the handle his right pinky actually hung off the butt-end, like a society matron sipping tea, the Babe swung and the ball rocketed toward right field. Giants outfielder Ross Youngs turned and ran, but halfway to the fence he stopped. The ball was still climbing. It bounced clear across the race track and rolled to a stop. A youngster retrieved the ball.

After the game, won by Boston 5 to 3, sportswriters asked Youngs to show them where Ruth's ball had come to rest. Laboriously, the writers paced the distance back to home plate.

The phrase "tape-measure shot" hadn't been invented yet, but it soon would be. The blast measured somewhere between 587 to 600 feet. Even Giants' manager John McGraw, a crusty old bird not given to hyperbole, called it "the longest ball I've ever seen hit."

It was the longest ball anyone could ever remember seeing hit. And by a pitcher! Later that evening, the ball--signed by Babe and Barrow--was presented to Billy Sunday at his tent.

Headlines in Saturday's Tampa Tribune screamed: "RUTH DRIVES GIANTS TO DEFEAT AND MAKES 'EM DRINK, TOO, B'GADS." The reporter, calling Ruth's homer a "wallop stupendous," wrote: "The Giants were still marveling last night. Many of them have never seen the Tarzan

perform since he annexed his slugging habits."

Monday, April 7, the Red Sox broke camp and headed north, barnstorming along the way with games in Gainesville, Winston-Salem, Charleston. In every town, huge crowds buzzed about mighty Babe and his blast. Frazee was becoming convinced: Babe needed to play every day.

During the 1919 season Babe pitched 17 games, but it was his final season on the mound. Playing outfield for Boston on days he didn't pitch, Ruth hit an astounding 29 home runs. That may not seem like much to today's fan. But consider: Before 1919, the single-season record for homers was 24, held by Gabby Cravath of the Philadelphia Phillies. In 1920, playing every day, Babe hit more homers (54) than any entire team in the American League! By the time he retired in 1935, Ruth had hit more homers than any man in the game's history.

Plant Stadium was razed in 2002 and replaced with a modern edifice, but a plaque on campus commemorates that historic swing of the bat on an April afternoon in Tampa, a swing that transformed the legend of Babe Ruth--and American sports--forever.

--Ken Brooks

Yesterday in Florida, Issue 18

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment